Written by: Megan Keville, Naturalist

If you come out with us at Orca Spirit you might be lucky enough to spot the most widespread mammal around the world after humans. The Orcinus orca or Killer Whale to some.

30 feet in length and male dorsal fins reaching up to 6ft tall, Orcas are a sight to take anyone’s breath away.

These black and white cetaceans are the largest species of the dolphin family. So, the question is why are they called Killer whales?

The name originally comes from ancient sailors who called them Asesnia ballenas which translates to Whale Killer. As this was passed through languages it believed the name was mistranslated and so Killer Whales were formed.

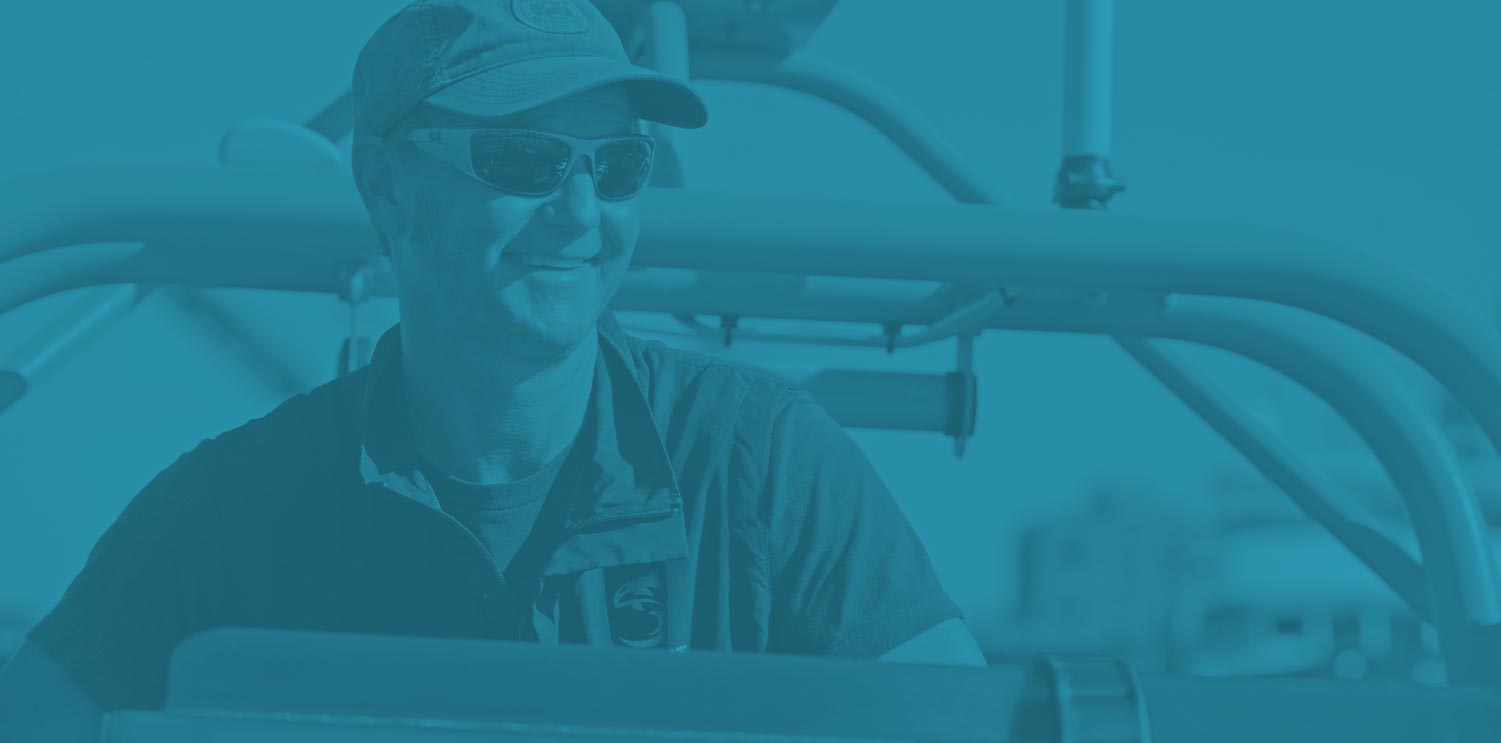

Figure 1: Biggs Killer whale (Orca Spirit, 2023)

Nowadays we know that not all Orcas eat marine mammals, such as our Southern Resident Killer Whales who feed on two of the five types of salmon in our waters. Our transient visitors however, the Biggs Killer whale, still do and during our summer season can sometimes be seen taking down a Humpback Whale calf as they migrate through our waters on their journey north.

As the Humpbacks are only temporary visitors, Biggs killer whales mostly feed on other Marine Mammals such as our Harbour seals and because of this they’ve developed a couple of interesting techniques.

All Odontocetes (toothed whales, dolphins and porpoises) hunt using a technique called Echolocation. This is a series or short high-pitched clicks that occur in a repetitive beam directed in front of the animal. These clicks bounce off the seabed, rocks, and other fish and the readings from this paint a picture for the animal about their surroundings.

Biggs hunt marine mammals who have acute underwater hearing. For example, Harbour seals can hear 14 times better under water than above. This means that they can hear the Orcas coming.

For this reason, the Biggs have been seen restricting this echolocation technique choosing to use sight and silent communication to hunt their prey. A study between 2008 and 2013 studied vocalisations in the Salish sea. During this time 184 Biggs killer whales were actively seen in the water but only 4 were heard using echolocation (Leu, A.A. et al. 2022). Another theory is that instead of restricting the use of echolocation Biggs Killer Whales have actually adapted the technique to produce less clicks in a time frame and at a lower frequency. This causes the noise to blend in with the background sounds of the ocean allowing the Biggs to be undetected by both our Hydrophones and their prey.

Figure 2: Biggs prey; The Harbour Seal (Orca Spirit, 2023)

Another interesting technique observed amongst Marine Mammal eating Orcas is Intentional Stranding. This behaviour consists of one or two members of the pod deliberately rushing the shore towards hauled out pinnipeds and temporarily becoming stranded in shallow waters. This is a risky behaviour and requires agile movement on the shore both to grab the prey and to unbeach themselves back into deeper water. This behaviour has been studied in Patagonia, where a small population of killer whales are passing down the technique from generation to generation. And also, in the sub–Antarctic Indian Ocean where the technique is being used to take down Southern Elephant Seals. However, before 2016 this behaviour had never been documented in the Pacific Ocean.

On the 14th of August scientists were watching one of the matriarchal pods (TO65A) hunting off Protection Island on the Strait Juan De Fuca. There for the first time ever they witnessed two members of the pod T65A (Matriarch of the Pod) and T65A2 (Eldest Son) repeatedly attempt to catch Harbour Seals by intentionally stranding themselves off the shore of Kanem Point (McInnes et al., 2020).

Although in this event, the success of the hunt was not directly related to this strategy it is amazing to see that this behaviour has also formed here in the Pacific Ocean.

These three pods around the world have never interacted. Each one has individually developed these behaviours themselves. And there are other Marine Mammal Eating Orcas who have never displayed this behaviour. It’s yet another example of how incredibly intelligent these charismatic animals are. They really are the Apex Predators of the ocean.

Figure 3: Biggs Killer Whale Breaching (Orca Sprit, 2023)

Want a chance to see these amazing behaviours yourself? Come #ExperienceTheWild with us at Orca Spirit Adventures.