Sometimes our whale watching guides in Victoria get asked questions on tours about ‘how whales came to be’? How long have they been roaming our oceans? Who are their ancestors? The discovery of fossils from around the world has unraveled the mysteries of how whales evolved and adapted to become the world’s largest animals who ever lived.

The closest living relative to whales- the hippo- doesn’t live in the ocean at all. In fact, the ancestors to all whales lived on land over 55 million years ago! The story gets even more strange with their genetic roots coming from hoofed land animals.

Let’s take a look at the whale family tree over geological time!

Pakicetus Attocki

Pakicetus attocki was a mostly terrestrial animal that lived during the Eocene period 55 to 33.9 million years ago. Their fossil remains have only ever been found in Pakistan which was a coastal region of Eurasia during the Eocene. It somewhat resembled a large dog but had ankle bones similar to a pig.

The feature that links this odd-looking creature to whales is a special thickened bone found in its skull called the auditory bulla. This bone is a specialized adaptation for hearing underwater and exists in all living whales today. Pakicetids did not have a large mandibular foramen in their lower jaw, which is a space found in the jawbones of modern whales that contains a fat pocket which aids in underwater sound absorption and thus hearing.

Ambulocetus natans

Ambulocetus natans was first thought to have spent most of its life in the water, but still capable of walking on land. However, more recent research suggests that it was likely fully aquatic. Fossils for this prehistoric whale come from the early Eocene approximately 49 million years ago. Ambulocetus fossils have been discovered in Pakistan and India.

Ambulocetus natans had short limbs and large feet that were likely used to paddle in the water. It may have undulated its back while swimming like modern whales. Ambulocetus natans was also like today’s whales in having no external ears and eyes on the sides of its head rather than at the top of their skull like the older Pakicetids did. It was also able to swallow underwater and could survive in both salt and freshwater. Their long jaw bones, pointed teeth and strong jaw muscles were likely used to bite their prey and kill it much like the hunting behavior of crocodiles.

Kutchicetus minimus

Kutchicetus minimus was a small otter-like species that lived in the early to middle Eocene between 43 and 46 million years ago. They belong to the Remingtonicetidae family, characterized by long snouts and long, powerful tails. Fossils have been excavated from the coastal border of Pakistan and India.

Kutchicetus’ powerful tail likely served as its main source of propulsion underwater, while undulating its body. It is believed that Kutchicetus could still walk on land, but its inner ear structure has lead scientists to believe they had poor balance in a terrestrial environment. They were likely very agile and acrobatic while in the water like today’s otters and dolphins. Because of their small eye sockets, they likely had poor vision but excellent hearing, adaptations fit for living in turbid waters like lagoons. Their blubber layer provided insulation and streamlined their body like modern whales.

Rodhocetus

www.flanderstoday.eu/innovation/face-flanders-protocetidae-zeebrugge

Two different species of Rodhocetus have been found in the fossil record and they belong to the Protocetidae family. Protocetids marked a new chapter in whale evolution and distribution. They are known as the cetaceans that conquered the oceans as their fossils have been found all over the world. Excavation sites of Protocetids include North and South America, Europe and Africa. This group of archaic whales are believed to be the first cetaceans to colonize new ocean habitats across the globe.

Protocetidae species lived 48 to 35 million years ago and are believed to have been amphibious, likely still giving birth on land but being predominantly aquatic. They had a large, powerful tail and feet, which would have allowed them to be excellent swimmers.

The nostrils of Protocetids had migrated further back on their snout, closer to their eyes, a first step towards the modern blowhole placement of today’s whales. Their hearing systems were intermediate between that of Pakicetids and today’s toothed whales. Their hearing above water would not have been exceptional and directional hearing underwater was likely not great either.

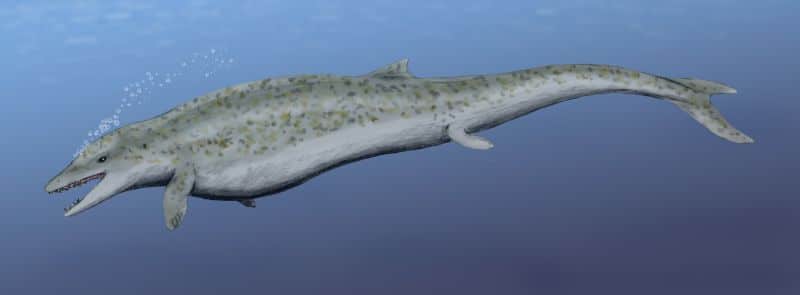

Basilosaurus

Basilosaurids and Dorudontines were fully aquatic prehistoric whales that lived in the late Eocene between 37 and 40 million years ago and were closely related to each other. From fossil remains, they likely inhabited tropical and subtropical seas all over the world. From a distance, they likely looked like today’s whales.

Bailosaurids and Dorudontines had nostrils positioned further up on their snout, more similar to the location of the blowhole(s) seen in modern whales. Their forelimbs had developed into flippers and their hind limbs had substantially decreased in size and length. Basilosaurids & Dorudontines no longer had their pelvis bone attached to their spinal column. This detachment of the pelvis allowed for increased maneuverability of the tail which was their main source of propulsion. Further support for their reliance on a tail to swim was squared off vertebrae at the tip of the tail which creates support for flukes as seen in whales that roam the oceans today.

Despite their similarities to modern whales, they still had not developed the melon organ, which today’s toothed whales possess to allow for echolocation. They also had small brains which could mean that they were solitary and lacked the complex social structures of many modern cetacean groups. Both ancestral whale types did have a mandibular foramen that extended the complete depth of the lower jaw as is found in today’s whales, which aids in sound absorption.

It is from the Durudontines that modern whales are believed to have directly evolved from. Today’s cetacean family is divided into two distinct forms- the mysticetes or baleen species and the odontocetes or toothed whales. The division between these two very different forms of cetaceans is believed to have occurred approximately 34 million years ago. Combined, there are almost 100 different species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises roaming the world’s oceans.

The story of life on Earth is full of adaptation and change. There is a constant battle between the changing environment and the ability of organisms to survive and thrive. Over time plants, animals, fungi and even bacteria & viruses need to adapt. Those best suited for the current environment are able to reproduce and spread their genes to the next generation. Eventually, whole new species are born and ancestral forms become extinct. The circle of life and change is never-ending, making our world an exciting place to explore and discover new things!

Make sure to check back with us for our next blog: The Evolution of Whales Part Two: The Division of Baleen (Mysticetes) and Toothed Whales (Odontocetes). Join us on a tour where you have the chance to see both baleen whales like humpbacks, grey whales and minkes and toothed whales like orcas, porpoises and dolphins! Learn from our naturalists about how all of these different species have adapted to their environment and how we can help ensure they swim the oceans for centuries to come.